Five Years of COVID: What Comes Next, Dr. Šalamon?

Originally published by Christian Klosz on Das Medium, this interview has been translated and republished with permission.

Five years into the COVID-19 pandemic: What are the current challenges, what mistakes were made, what needs to improve, and how will the situation evolve in the coming years?

A conversation with Špela Šalamon.

Dr. Špela Šalamon is a specialist in nuclear medicine, working at a regional hospital in Styria. She also serves as an expert for the WHN and the Vienna Medical Association. The interview was conducted by Christian Klosz.

At the moment, COVID-19 case numbers (based on statistical estimates of the “real incidence”) are relatively low compared to previous years. Is this just a temporary trend, or can we draw conclusions for the future?

“‘Low’ is a relative term—in fact, since the lifting of restrictions, annual infection rates, as estimated from wastewater data, have consistently been higher than in 2020. Many countries have drastically scaled back their testing strategies, leading to an underestimation of the virus’s true spread. That’s why we have to rely on statistical calculations. SARS-CoV-2 continues to mutate, and new variants could trigger fresh waves of infections, especially if they develop immune escape mechanisms.

The currently low incidence can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, no new variants have emerged in our region recently. Secondly, reduced social interactions—due to inflation or chronic illness—could also play a role. Even when new variants exhibit immune escape properties, a recent infection often provides at least some protection for a few months. Additionally, infection rates were particularly high in summer and autumn 2024, which could also be influencing the current numbers.”

What percentage of people do you estimate are affected by Long COVID, ME/CFS, and other debilitating consequences of COVID-19 infections?

Based on current studies and the review paper “Review of Organ Damage from COVID and Long COVID”, which I contributed to, estimates vary depending on definitions and the population studied:

- Approximately 10–30% of non-hospitalized individuals develop Long COVID symptoms after an infection. With each additional infection, this number cumulatively increases by another 10–15%. In hospitalized patients or those with severe cases, the rates are even higher—exceeding 50%.

- Organ and vascular damage without obvious symptoms—sometimes referred to as PASC (Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19)—affects more than 50% of those infected. This includes damage to the cardiovascular system, brain, lungs, and immune system. Some estimates suggest that the figure could be 70% or higher, particularly when subclinical damage is also considered.

- Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and post-exertional malaise (PEM) have become increasingly common after COVID-19. Overall, the percentage of individuals who remain severely affected could range between 1–5% of all infected persons, and this number likely increases with reinfections.

Why do you think Long COVID has been largely ignored by many medical professionals, the media, and policymakers?

The issue remains highly unpopular, especially among those who rely on votes. Many governments have declared COVID-19 “over” (despite this being untrue by any definition) and fear that acknowledging its long-term consequences would be seen as a political admission of failure. Recognizing the full extent of the damage would come with enormous financial implications for social security and healthcare systems—ranging from early retirements to long-term care and workforce losses. However, the long-term cost of continued neglect will likely be far greater. A persistent pandemic means ongoing disruptions for businesses, whether due to infection control measures or the recognition of workplace-related infections as occupational illnesses.

Diseases such as ME/CFS, Long COVID, and fibromyalgia have often been dismissed as psychosomatic in the past, and this perception persists among many medical professionals and institutions. Many Long COVID sufferers are no longer able to work, are socially isolated, or experience severe daily limitations—leaving them with little opportunity to make their voices heard in the media or political discourse.

Despite the growing body of research, it often takes years for new findings to be incorporated into clinical guidelines and practice. While there is increasing evidence of objective biomarkers—such as microthrombotic changes and immune and vascular damage—there is still no standardized test for Long COVID or ME/CFS. This makes diagnoses both difficult and vulnerable to skepticism. Furthermore, many healthcare providers have not received sufficient education on Long COVID and ME/CFS, leading to frequent misdiagnosis or dismissal as a psychosomatic condition.

The disregard for Long COVID is not accidental; rather, it is the result of a complex interplay of medical, societal, and political factors. While scientists and affected individuals are increasingly raising awareness, the response from many decision-makers continues to lag behind the scientific evidence. In the long run, this negligence could have serious repercussions—not just for the healthcare system, but for society as a whole.

Is there a connection between the negative economic developments in many countries and these health issues?

Yes, there is a clear connection between the economic downturn in many countries and the long-term health consequences of COVID-19, including Long COVID and related work disabilities. Estimates suggest that millions of people worldwide are either unable to work or significantly limited in their work capacity due to Long COVID. As mentioned earlier, studies indicate that 10–30% of those infected develop Long COVID, with up to 5% potentially becoming permanently or long-term unable to work. This results in massive productivity losses across various industries, particularly in healthcare, education, and the service sector, where long-term absences are especially problematic.

Businesses are struggling with higher absenteeism, increased resignations, and a growing need for new hires, part-time work, and retraining. Many Long COVID sufferers experience reduced income and higher healthcare expenses, leading to decreased purchasing power. This, in turn, dampens private consumption, negatively impacting retail and the service sector. Industries such as travel, hospitality, and the cultural sector are particularly affected, as many individuals with Long COVID have reduced mobility and activity levels.

COVID-19 can also accelerate biological aging, increasing the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disorders, and diabetes. A weakened workforce and a growing burden of illness will lead to higher healthcare costs and a less productive population in the long run. While the economic crisis in many countries is not solely caused by COVID-19, the pandemic’s lasting effects are exacerbating existing challenges such as labor shortages, inflation, and a deficit of skilled workers.

What solutions do you believe are necessary?

A multidimensional, science-based approach that takes medical, social, and economic factors into account. Here’s an overview of the key priorities:

- Public awareness: The long-term health impacts of COVID-19 must be communicated transparently and based on scientific evidence to prevent misinformation.

- Education for healthcare professionals: Doctors and medical staff need better training on Long COVID, post-viral syndromes, and effective protective measures.

- Improving indoor air quality: Clean air in enclosed spaces is crucial to reducing transmission. This includes HEPA filters, UV-C lamps, CO₂ monitoring, and improved ventilation systems.

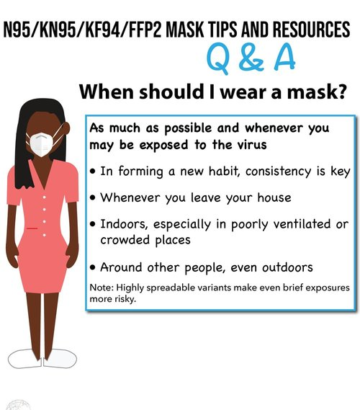

- FFP2/N95 masks in high-risk areas: Especially in healthcare facilities, pharmacies, nursing homes, schools, and public transport.

- Specialized Long COVID clinics: Interdisciplinary teams of trained diagnosticians, neurologists, immunologists, cardiologists, and rehabilitation specialists are essential.

- Targeted development of treatment strategies: Research into antiviral treatments, immune modulation, rehabilitation measures, and potential therapies for persistent viral reservoirs.

- Long-term patient care: Those affected need continuous medical support, not just short-term rehabilitation programs.

- Flexible work models: Remote work options and reduced hours must be more accessible. This would also have positive effects on the environment, productivity, and quality of life.

- Recognition as an occupational disease: COVID-19-related work disability should be officially recognized by health insurance and pension systems.

- Financial support for affected individuals: In many countries, Long COVID patients face excessive bureaucratic hurdles—this needs to be simplified.

- Supported isolation and quarantine: Many infected individuals cannot effectively isolate at home. The option for isolation with (tele)medical supervision could help prevent further infections and complications.

- Long-term data monitoring and pandemic preparedness: Early warning systems using wastewater analysis and sampling, rapid adaptation of protective measures, and clear communication strategies.

- Promoting international cooperation: COVID-19 is a global issue—solutions must be developed and implemented on an international scale.

Where do you see society in 1, 5, and 10 years—even if the pandemic phase comes to an end? Will these long-term effects still play a role?

Since I prefer to remain optimistic, I will offer my hopeful prediction—one that does not include the collapse of civilized society due to widespread neurological impairment.

- Short-term—within 1 year: Despite declining public attention, millions will continue to suffer from Long COVID, vascular damage, and neurocognitive impairments. Essential professions, such as healthcare, education, and caregiving, will see increasing absenteeism and early retirements. Most governments will continue to downplay the issue to avoid financial burdens. Initial targeted treatments for Long COVID may be tested in small specialized centers, but widespread access to care will remain inadequate.

- Mid-term—by 2030: An increasing number of people will develop long-term cardiovascular, neurological, and autoimmune conditions, similar to the post-polio wave following the Spanish flu. Rising cases of early disability and work incapacity will place growing strain on pension and social security systems. Long COVID will finally be recognized internationally as a chronic illness. Advances in treating persistent viral reservoirs and immune modulation could lead to the first truly effective therapies. Gradually, a broader understanding will emerge that air quality, vaccine technology, and antiviral prevention are key to long-term public health.

- Long-term—by 2035: Delayed complications will contribute to a permanent reduction in life expectancy and a rise in diseases such as heart attacks, strokes, dementia, and chronic fatigue. Specialized treatments and multidisciplinary approaches for post-viral syndromes will become standard practice. Demographic shifts will be exacerbated by a shrinking pool of healthy workers, rising healthcare costs, and continued productivity losses. Eventually, a societal shift will take place, recognizing public health and air quality as essential priorities—much like clean water and hand hygiene became fundamental after past pandemics. This transformation will better prepare us for future infectious diseases and may finally enable the suppression and elimination of COVID-19.

Why do you think the negative consequences of the pandemic are largely ignored by much of society?

Many people have been infected multiple times—along with their children and loved ones—and do not want to believe that this could have caused serious or irreversible damage. The idea that governments or healthcare systems may have made mistakes is unsettling, so the brain naturally filters out conflicting information. The desire for “normalcy” often outweighs concerns about health risks, even when those risks remain.

From an evolutionary perspective, humans respond more strongly to immediate dangers (such as fire) than to slow-moving threats (like long-term damage from viral infections). Since COVID-19 is no longer perceived as an acute threat—especially after widespread vaccination—its long-term consequences feel abstract and easy to ignore. Those who continue to wear masks or discuss Long COVID are often seen as “overly anxious” or “stuck in the past.” Social conformity also plays a role—once the collective narrative becomes “the pandemic is over,” it becomes socially uncomfortable to challenge that belief.

Our society is productivity-driven, and chronic illnesses like Long COVID or ME/CFS do not fit into that framework. Many Long COVID patients are dismissed as “mentally ill” simply because the condition is difficult to diagnose. Additionally, major media outlets have significantly reduced their coverage of COVID-19 over the past 2–3 years. This has created the illusion that the problem no longer exists—reinforcing societal denial while leading to misinterpretations of new health issues as “mysterious” conditions, or even as supposed “vaccine injuries” or “lockdown aftereffects.”

What individually observable health issues could be linked to COVID? What advice do you have for those who notice that “something isn’t right” after an infection?

Honestly—almost anything. The virus primarily affects blood vessels, especially the small ones that supply all organs with blood, nutrients, oxygen, and immune defense. Organ damage leads to reduced function and physiological reserve, which in turn decreases overall health, shortens life expectancy, and increases vulnerability to future infections and diseases. It can also result in acute events such as heart attacks, strokes, and recurring infections of other kinds.

Organ damage plays a major role in Long COVID symptoms. In many ways, Long COVID can be seen as just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to multisystem and organ damage. Some of the most common issues include fatigue and reduced stamina, shortness of breath, body aches, heart palpitations, sleep disturbances, internal tremors and nervousness, memory and cognitive problems, as well as a tendency to develop frequent infections.

My most important advice: Avoid reinfections at all costs! For those already experiencing long-term effects, reinfections typically result in a further decline in baseline health and worsening symptoms. However, without reinfections, it is possible for health to improve over time with patience and proper rest.

Austria recently formed a new government, which—at least in its policy program—has committed to improving care for ME/CFS patients. During the election campaign, the SPÖ also advocated for “clean air for all.” Do you think the government and responsible ministries—after the disastrous years under Health Minister Rauch—will take meaningful steps in the right direction?

The announced improvements in care for ME/CFS patients are a step in the right direction. However, it remains to be seen whether these promises will actually translate into concrete actions. In the past, political commitments in healthcare have often been implemented half-heartedly—or not at all.

Former Health Minister Johannes Rauch (Greens) made little effort in this area over the past years. His disregard for masks—even when interacting with highly vulnerable individuals such as infants and critically ill patients—set a disgraceful, uninformed, and irresponsible example. His mishandling of Long COVID and ME/CFS further eroded public trust. The current state of care for ME/CFS patients is catastrophic, and real improvements will require significant investment in research, diagnostics, and treatment. Political promises often serve more as symbolic gestures than genuine commitments, and based on my experience with politics, I remain skeptical.

The SPÖ’s campaign pledge for “clean air for all” could be an indirect acknowledgment of the importance of air quality in preventing infections—an issue that is critical for ME/CFS and Long COVID patients. The new government may seek to distance itself from past failures and take targeted measures to regain public trust. However, real progress will largely depend on sustained public pressure from advocacy groups, doctors, and researchers.

What is your personal conclusion after five years of the COVID-19 pandemic, both medically and socially?

Before the pandemic, I firmly believed that the people leading international medical conferences, major medical institutions, and political health committees were highly educated experts in their fields. Now, the emperor has no clothes. Anyone who has followed the science even slightly can see that many of these so-called experts are merely playing the part—and they are not going to “save” us. We must stay informed and take responsibility for protecting ourselves and each other. For now, we can expect only limited help from our political leaders. True security and resilience can only be built from the ground up—through grassroots communities and direct engagement with what remains of unbiased, apolitical science, free from conflicts of interest.

Through this pandemic, those of us who understand the scientific and medical realities of this disease have seen people’s true nature—within our families, among friends, colleagues, doctors, and leaders. It can be unsettling to realize how many of them have shown negligence, incompetence, or even outright malice. But gaining the ability to distinguish the good from the bad and the ugly is invaluable.

I encourage everyone to find the courage to face reality and adjust their lives accordingly. There is no need for fear or panic when we understand what lies ahead and how to protect ourselves. In fact, it is those who persist in denial who are truly living in fear.

Thank you for the interview!

Dr. Špela Šalamon, MD, specialist in nuclear medicine, is a physician and biomedical scientist specializing in the genetics of complex and degenerative diseases. In her research, she aims to track disease progression from the genetic level through molecular, cellular, tissue, and organ changes, ultimately leading to clinical manifestations—with the goal of understanding and controlling every possible step of the disease process.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, she has served as a volunteer scientific advisor for the World Health Network and is an editor of the journal WHN Science Communications. She has also published multiple papers on the health risks associated with COVID-19 infections.