Opinion: Pretending It’s Over Amplifies the Pandemic

In a chaotic world where a nuclear power entered a war of choice, and multiple mass shootings have grabbed our attention, the ongoing pandemic is receding from the headlines. But try as we might, ignoring the virus in our global game of peek-a-boo isn’t working.

In recent months, the Biden administration has crowed about falling case numbers. But those figures were artificially lowered by the shift towards at-home tests, most of which aren’t tracked, and such tests reportedly miss up to 40% of infections. They also dropped support for subsidized PCR tests, and repeatedly doled out at-home tests, which furthered the shift towards at-home testing. (That they didn’t provide a mechanism for reporting results with those tests suggests a desire to hide them from the totals.) Given those factors, our case numbers are significantly minimized, and many people are likely not isolating or seeking treatment due to false negatives, thereby fostering additional transmission. The lack of insight harms our ability to adapt to the circumstances and leaves public health officials guessing.

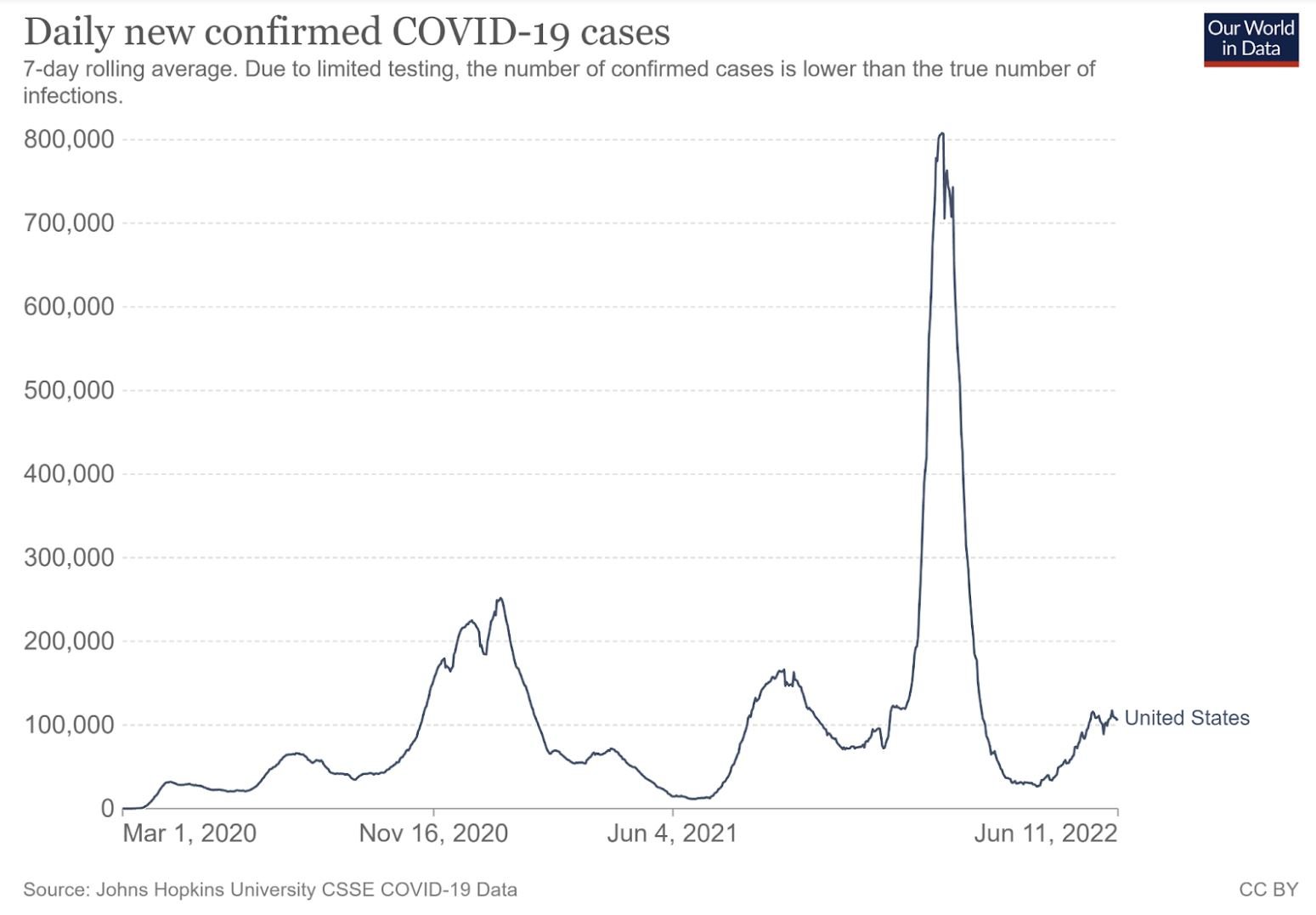

And while cases dropped precipitously for weeks, the trend reversed with the BA.2 variant.

Daily new confirmed COVID-19 Cases in the United States

A new study sampled 1,030 adult NYC residents from April 23 to May 8, 2022. It has yet to be peer reveiwed, so caution should be taken in interpreting the results, but 22% of respondents tested positive during the study period. This roughly equated to 1.5 million cases for the city, while official statistics had the number at 49,253. The disparity left Denis Nash, one of the study’s authors and a CUNY professor of epidemiology, incredulous. As he put it, “It would appear official case counts are under-estimating the true burden of infection by about 30-fold, which is a huge surprise.” The same team did a similar study from January to March and found a fourfold discrepancy between official statistics and their estimates at the time. While it may be hard to accept the new study’s findings, the growing data gap seems assured.

As the Omicron wave left, the CDC began to muddy the waters. Its Community Transmission tracker was long a primary tool for assessing the state of the pandemic via a ratio of case levels to population. During the Delta and Omicron waves, most of that map turned red with states having high transmission rates. In late February, just days before the State of the Union address, the CDC removed that map from its COVID Data Tracker homepage and replaced it with its new COVID-19 Community Levels tracking. The new map focuses on the trailing indicator of local hospitalizations. The CDC recommends that we use the new tool “to determine the impact of COVID-19 on communities and take action,” while the Community Transmission data is only intended for use by healthcare facilities.

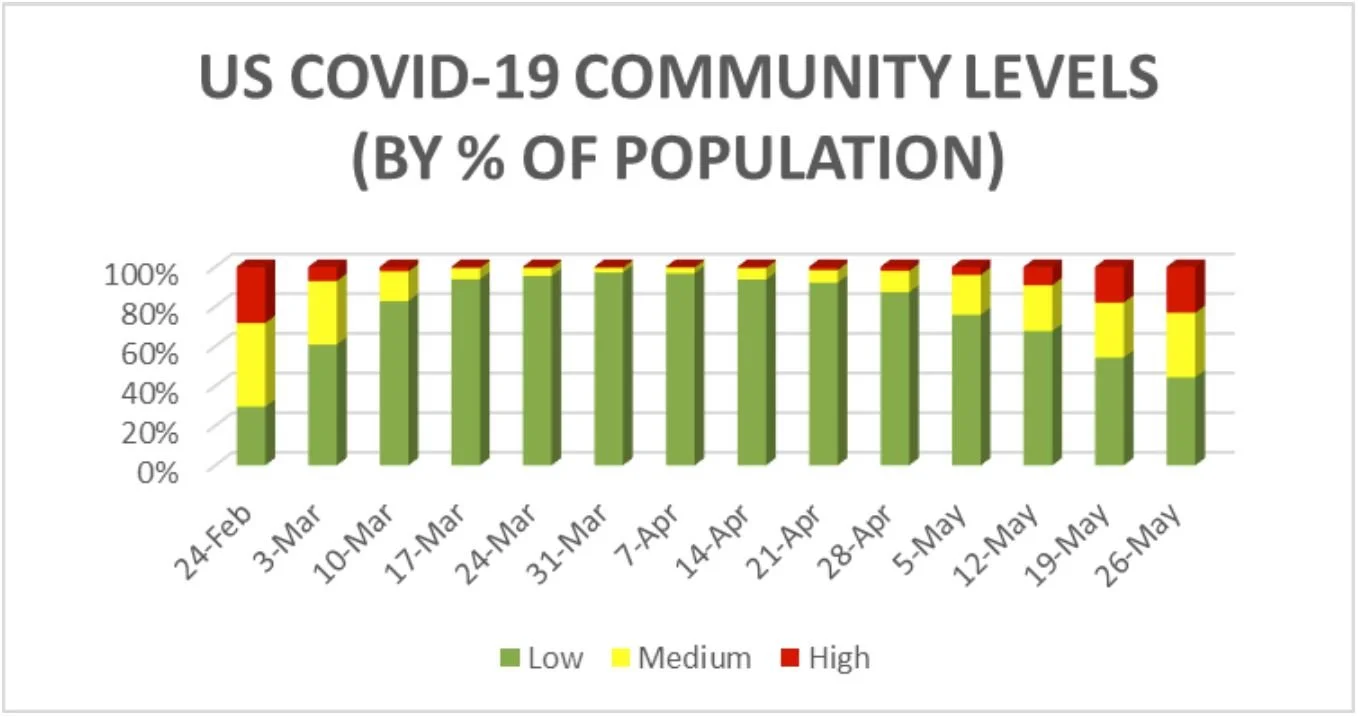

The COVID-19 Community Levels dashboard has three categories: low, medium, and high. Depending on which page on the CDC site you visit, you get very different guidance for those categories. One offers high-level suggestions that recommend that everyone gets a booster, and get tested if they have symptoms. The guidance recommends that immunocompromised people in medium counties talk to their healthcare provider about whether they should “wear a mask and take other precautions.” It also recommends masks for everyone in high counties. The guidelines suggest more precautions for each level, but those are buried on a page that most people will never visit. The approach seems designed to offer helpful guidance to the people concerned enough to dig past the surface — or at least to provide the alibi of having such information ‘available’ — while leaving the bulk of the site’s visitors with the impression that all’s well.

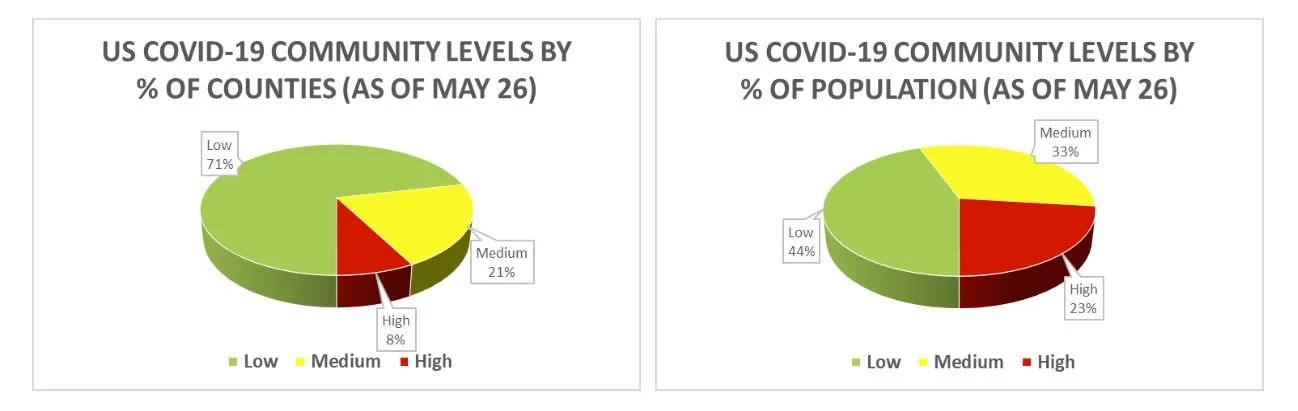

On May 27, CDC Director Walensky shared a post on Twitter noting that “Over 55% of the U.S. population is in an area with a medium or high COVID-19 Community Level.” The map displayed on the Community Levels page looked the same as the one shared by Director Walensky, but with one crucial difference. Rather than displaying the % of the US population in each category, the dashboard’s map instead shares the percentage of counties in each category. The map on the dashboard presented a reassuring 71% of counties being low, while just 44% of the population lived in low counties. It’s worth questioning why the former is the default, and the latter is not accessible from the dashboard.

The CDC’s Community Levels by % of Counties and % of Population (as of May 26).

In early 2021, the CDC warned that we needed “enhanced genomic surveillance combined with continued compliance with effective public health measures, including vaccination, physical distancing, use of masks, hand hygiene, and isolation and quarantine” to limit the spread of COVID-19. In 2022, if you’re not in a county that’s rated high, you’re told to figure it out for yourself. As long as that’s the approach, we’re left hoping that the virus that’s continually replacing itself with new variants, stops mutating and eventually burns out.

An annual gala held in Washington, D.C. put the CDC’s problematic guidance under the spotlight as it became a superspreader event that sent home at least eighty attendees with COVID-19 — including two cabinet members and the mayor of New York City. The event was held while the CDC’s Community Level indicator for the county was medium, leaving invitees to determine whether to attend and what precautions, if any, to take. Meanwhile, the county’s healthcare facilities were on red alert thanks to the Community Transmission tracker.

The Guardian published an opinion following the launch of the Community Levels dashboard from a group calling itself the People’s CDC, a group of concerned epidemiologists, nurses and physicians, artists and biologists. Their op-ed claimed that the CDC’s new guidelines went against evidence-based, equitable public health practice in three critical ways. They believed the new policies did not aim to prevent the spread of disease, that the changes shifted the burden of responsibility onto vulnerable people, and that those choices were blatantly political. They also countered the idea that the White House and the CDC were trying to prevent infection and suffering, as they claimed that the people who are charged with protecting us have “put the desires of corporate America above the needs of our people, and especially our most vulnerable.”

The next day, CDC Director Walensky announced that an outsider would undertake a review of the organization, but given the circumstances, it felt like an excuse. For instance, back in July 2021 as the Delta wave gathered steam, an internal CDC document warned, “Given higher transmissibility and current vaccine coverage, universal masking is essential to reduce transmission,” but the CDC’s leaders did not call for such measures. And in late May, just days before Director Walensky shared the worrisome state of the Community Levels map, the CDC shared that 20% of adults “experience a new condition a month or more after surviving COVID-19.” This confirmation of the prevalence of long COVID provided additional justification for limiting transmission at a time when cases were again on the rise. But there was no change to the guidance. It seems unlikely that a review of the CDC’s structure, systems, and processes would help get CDC leaders aligned with their scientists’ recommendations. The problem is not a matter of structure, but one of priorities. As long as the appearance of control is prioritized over reducing transmission, many will needlessly suffer.

State-level officials also contributed to our challenges as they declared they were in the endemic stage, which suggested we’d no longer see the sorts of case surges that have become common. (Missouri’s governor notably made the shift on April Fools Day.) In reality, it means we’re making changes to things like definitions, data reporting, and contact tracing procedures, which leave us more in the dark about our circumstances and put us at greater risk of future waves.

News out of New Hampshire brings hospitalization data into question. In March, the state’s government changed their tracking of COVID-19 hospitalizations to only include patients that were actively being treated with Remdesivir or Dexamethasone. The Biden administration backed the move, and it was reportedly “part of a national trend.” At the time, the state’s hospitals reported 104 hospitalizations, with thirty of those still being infectious, while the state’s government reported seven cases. In response to the change, a New Hampshire Hospital Association spokesperson warned: “The total number of people hospitalized with confirmed COVID-19 is one of the most important metrics in monitoring the severity of illness and the prevalence of COVID-19 in the state.”

Examples of other states with recent reporting changes abound. In Indiana, the Department of Health reduced updates on its COVID-19 dashboard to three times a week from five. Illinois shifted to weekly updates. Florida reduced theirs to bi-weekly. Oklahoma stopped counting cases that were not promptly reported in new case totals. The latter move allowed the state to report 400 new cases, while over a thousand were ignored due to their test date.

In April, the new White House’s COVID-19 response coordinator, Ashish Jha, stated, “If you think about where we are as a country, we are at a really good moment.” At the time, both the Community Level ratings (% of counties and % of the population) had around 94% rated low. Meanwhile, just 15% of counties were low in the Community Transmission tracking as of April 29. The CDC was putting healthcare facilities in three-fourths of US counties on notice while doing the same for the people in less than 5% of our counties. How can that make sense from a public health standpoint? Given that the percentage of the population living in low counties has dropped from 94% to 45% in six weeks, it seems we squandered the moment.

Along with moving the goalposts, the introduction of the Community Levels tracking coincided with changes that pushed authority for implementation down to the county level. It treats vaccines as a quick techno-fix while ignoring the complex, systemic nature of the pandemic. At best it embodies hope as a strategy, but it increasingly feels like abandonment. Rather than fighting for public health measures, the CDC’s leaders have abdicated their responsibility.

On top of this, the focus on hospitalizations is a reactive approach that counters the public health principle of prevention. Hospitals are at the end of the line. They get us when we’re already sick. They don’t do the work that helps us avoid the virus. That’s the job of public health.

Before the CDC introduced the COVID-19 Community Levels rating system, any county with fifty or more new cases per 100,000 people was rated substantial or high. The new system had the District of Columbia rated low in April with 142 new cases per 100,000 people (and medium in May with 298 cases per 100,000). So aside from the hospitals, it was an all-clear message in D.C., but if the county’s hospitals start to fill up, the CDC will eventually tell everyone to put on a mask.

On April 18, a Trump-appointed federal judge struck down the TSA’a mask mandate. In doing so, they argued that the claim that masks were required for sanitation purposes was invalid. As the judge put it, “Wearing a mask cleans nothing. At most, it traps virus droplets. But it neither ‘sanitizes’ the person wearing the mask nor ‘sanitizes’ the conveyance.” The decision suggests bad faith or a limited understanding of the term.

The Justice Department announced that it would appeal the judge’s ruling, assuming an ongoing assessment from the CDC determines “the order remains necessary for public health.” Meanwhile, the number of TSA workers infected with COVID-19 jumped from 359 on the day the mandate ended to 542 just a few weeks later.

While the US is in yet another wave, our immunizations will reduce suffering, but over a third of humanity has yet to have their first shot, and just 16.2% of people in low-income countries have received any doses. Moreover, immunization can only do so much for the immunocompromised, and they can’t protect young children who are not yet eligible to receive vaccines.

On April 1st, WHO Director-General Tedros Ghebreyesus released a short video, in which he asked if some lives are worth more than others as he called for vaccine equity for all of humanity. As he put it, that “remains the single most powerful tool we have to save lives.”

Getting effective vaccines to everyone who wants them as quickly as possible is a necessary step towards ending the pandemic, but primarily focusing on vaccination is a poor approach to public health. The UK’s experience with the BA.2 Omicron variant provides jarring proof. The nation had 82% of its adults with three doses of COVID-19 vaccines, and 99% of them had antibodies (including those who had had infections). Still, the UK recorded its highest level of infections in the same period.

Citizens of the UK might ask themselves if this was what they expected back in February when Boris Johnson removed the nation’s remaining restrictions. As he did so, he claimed that “all the efforts of the last two years finally enabled us to protect ourselves while restoring our liberties in full.” He and his contemporaries have made many claims throughout the pandemic, but the results are clear. We can repeatedly declare independence from the pandemic, but we won’t free ourselves of it with our current priorities.

Boris Johnson’s administration has long been the standard-bearer of the laissez-faire approach to public health that has been mirrored in the US and cost us millions of lives and immeasurable suffering around the globe. We should never have allowed it, yet we continue to do so.

Back in the US, the CDC is prioritizing political goals over public health. At the end of February, they proclaimed that the majority of us were in places where we could take our masks off. Now, as we enter the Memorial Day weekend with six times as many cases as the prior year, they’re staying out of the decision until things are out of hand. We shouldn’t be surprised by this. A political appointee leads the agency, so conflict of interest is there by design. The OECD warns of such dangers. Throughout the pandemic, it has become increasingly difficult to avoid the conclusion that conflict of interest is at play, as the political motivation has been clear each time Director Walensky has made a confounding decision.

We know the virus is still circulating and mutating.The BA.2.12.1 variant just eclipsed BA.2 in the US, while BA.4 and BA.5 are wreaking havoc elsewhere We recently hit 1 million official deaths in the US, and we know the actual figure is well above that. Our vaccines do not prevent infection or transmission and they weren’t designed for the variants we’re now dealing with. Why aren’t we pursuing new vaccines that aim for the current need? And more generally, why isn’t the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention throwing everything it has into controlling and preventing this disease?

Early in the pandemic, leaders in the US chose the path of mitigation over elimination, and they have repeatedly doubled down on that choice. But you can’t appease an exponential curve. If you believed otherwise early on, lived experience has surely taught you otherwise. It’s time to demand that we work to reduce transmission. The costs of doing so, in terms of things like accepting the inconvenience of mask-wearing and sharing the burden of improving air quality in enclosed common spaces seem a small collective sacrifice in light of the suffering it can help us avoid.

New variants compound uncertainty. They might bring greater virulence, increase transmissibility, reduce vaccine efficacy, and render our tests less effective or useless. They also put us at risk of new surges. When they appear, the tendency has been to wait and see, looking for conclusive evidence before acting. This approach has repeatedly amplified waves. Working to mitigate transmission would blunt those surges, while reducing the chance of problematic variants becoming viable. We need our leaders to stop worrying about inconveniencing community members and get them refocused on the job of keeping us safe.

Our public health experts know what to do. We have to give them the support they need to point us toward the pandemic’s end. Failing to do so devalues our shared humanity and answers Dr. Tedros’ question in the affirmative. That’s a damning prospect we should not want as our legacy. Instead, it’s time to require better of ourselves and our leaders. They won’t change without a demand. It’s time we demand it.