“Common Names” for Notable SARS-CoV-2 Variants: Proposal for a Transparent and Consistent Nicknaming Process to Aid Communication

T. Ryan Gregory, Yaneer Bar-Yam, Ulrich Elling, Daniele Focosi, Ryan Hisner, Mike Honey, Stuart Turville

First draft: October 1, 2022;

Updated: February 13, 2023 and August 24, 2023

I. Executive Summary

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has highlighted the importance of clear communication that makes information accessible to a wide audience. Efforts to communicate about the evolution, diversity, and importance of SARS-CoV-2 variants has become increasingly challenging as the number of variants has expanded dramatically, especially since mid-2022. Formal naming systems that are currently in place — namely Greek letters assigned by the World Health Organization (WHO), technical Phylogenetic Assignment of Named Global Outbreak (PANGO) labels, and Nextstrain clades — do not provide options for communication that is both sufficiently high resolution easily accessible outside of technical discussions. Here, we summarize the basis of existing nomenclature systems and propose a complementary option based on informal “common names” or “nicknames” that can be used in general scientific communication about variants. This follows several months of positive experience using a loosely defined system of nicknames on social media that used Greek mythological creature names to highlight variants of particular importance. It is suggested that a more transparent, consistent, and informative system of common names be implemented based on astronomical names chosen in such a way as to indicate details about variant evolution (i.e., major lineage, and whether it or its ancestor arose via recombination).

II. Background

The names used in communicating about SARS-CoV-2 have been important since the earliest days of the pandemic. For example, it was noted at the outset on that geography-based names are problematic in that they promote xenophobia, and even some technical names were avoided in order to reduce associations with past disease outbreaks. Notably, the World Health Organization (WHO) decided in February 2020 to refer to the disease as “COVID-19” (“coronavirus disease 2019”) rather than “SARS2” (“severe acute respiratory syndrome 2”, and to use “the COVID-19 virus” in place of “SARS-CoV-2” (“SARS coronavirus 2”) in most public communications:

From a risk communications perspective, using the name SARS can have unintended consequences in terms of creating unnecessary fear for some populations, especially in Asia which was worst affected by the SARS outbreak in 2003. For that reason and others, WHO has begun referring to the virus as “the virus responsible for COVID-19” or “the COVID-19 virus” when communicating with the public. Neither of these designations are intended as replacements for the official name of the virus as agreed by the ICTV. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it

In addition to the initial waves of infection and associated hospitalizations and deaths caused by “wild type” SARS-CoV-2 (perhaps better known as the “original” or “ancestral” SARS-CoV-2), multiple waves have been driven by the evolution and spread of new variants. In spring 2021, WHO sought to develop an accessible naming system to aid in communication about emerging variants, with two primary objectives: 1) to prevent the use of geography-based names (e.g., “the South African variant”, “the variant from the UK”), which could lead to xenophobia aimed at countries where variants are first identified (but not necessarily where they evolved) and potentially discourage the release of timely variant surveillance data, and 2) to simplify communication about variants in non-technical discussions (cf. PANGO lineage labels such as “B.1.1.529”; see below). In late May 2021, WHO announced a system by which new variants could be identified as “variants of interest” (VOI) or, if they meet additional criteria, “variants of concern” (VOC). To facilitate broader communication about these variants, VOIs and VOCs were granted a label based on the Greek alphabet.

According to a WHO announcement on May 31, 2021 (https://www.who.int/news/item/31-05-2021-who-announces-simple-easy-to-say-labels-for-sars-cov-2-variants-of-interest-and-concern):

WHO announces simple, easy-to-say labels for SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Interest and Concern

WHO has assigned simple, easy to say and remember labels for key variants of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, using letters of the Greek alphabet.

These labels were chosen after wide consultation and a review of many potential naming systems. WHO convened an expert group of partners from around the world to do so, including experts who are part of existing naming systems, nomenclature and virus taxonomic experts, researchers and national authorities.

WHO will assign labels for those variants that are designated as Variants of Interest or Variants of Concern by WHO. These will be posted on the WHO website.

These labels do not replace existing scientific names (e.g. those assigned by GISAID, Nextstrain and Pango), which convey important scientific information and will continue to be used in research.

While they have their advantages, these scientific names can be difficult to say and recall, and are prone to misreporting. As a result, people often resort to calling variants by the places where they are detected, which is stigmatizing and discriminatory. To avoid this and to simplify public communications, WHO encourages national authorities, media outlets and others to adopt these new labels.

By mid-2022, the situation with variant evolution had become considerably more complex, with hundreds of (sub)variants identified, all of them falling within “Omicron”, which was the last new Greek letter assigned by WHO in November 2021. This has meant that non-technical discussions of the most important variants have only two formal naming options: WHO Greek letters (which is all currently “Omicron”) or an increasingly complex collection of PANGO lineages, in many cases now several layers of “aliases” deep. The same communication challenges therefore apply now as they did in spring 2021, though now there are hundreds of variants with which to contend, and more evolving rapidly.

III. Current Naming Conventions

A consistent nomenclature can serve different goals and follow different guiding principles and rulesets, so it is perhaps not surprising that several parallel nomenclatures have been established for SARS-CoV-2 over the course of the pandemic. For example, a naming system may aim to achieve one or more of the following:

- Improve communication with the general public. The Greek letter naming scheme implemented by the WHO aims to achieve this.

- Catalogue variants with unique mutations, and capture evolutionary relationships among variants. The PANGO designation system does this (at least when referring to full labels rather than simplified aliases).

- Highlight the most notable subset of designated variants. Nextstrain labels seek to accomplish this.

- Indicate the time of first appearance of new variants. Nexstrain labels and an independent system implemented in the UK aim to do this.

The various naming systems already in place — including the WHO Greek letter system for VOIs and VOCs, Phylogenetic Assignment of Named Global Outbreak (PANGO) lineages, and Nextstrain / CoVariants clade designations — each serve a different purpose and follow different criteria and naming conventions. The basis of each of these is reviewed in the following sections.

III.1. WHO Nomenclature

During a period of ~180 days between May and November 2021, the WHO assigned Greek letter names to 13 variants, including eight Variants of Interest (Epsilon, Zeta, Eta, Theta, Iota, Kappa, Lambda, Mu; https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/previously-circulating-vois) and five Variants of Concern (Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, Omicron; https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants). (Note that Nu and Xi were omitted from the sequence between Mu and Omicron in order to avoid confusion with the word “new” and a common surname, including the name of Chinese leader Xi Jinping; https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/28/world/asia/omicron-variant-name-covid.html).

The WHO updated the working definitions of VOIs and VOCs March 15, 2023, indicated that only the original “Omicron” (B.1.1.529) was a VOC and downgraded it to a formerly circulating VOC, and indicated that only VOCs and not VOIs would receive new Greek letters moving forward. Working definitions were revised again August 17, 2023 in part due to the emergence of the highly mutated BA.2.86 variant.

No new VOIs or VOCs have been granted a Greek letter name since the emergence of Omicron in November 2021. The lack of new Greek letters (the next of which would be “Pi” and “Rho”) has been misinterpreted by some to mean that there are no important differences among circulating and emerging variants (“Omicron is Omicron”, “it’s all Omicron”). Far from having slowed, SARS-CoV-2 variant evolution has generated a bewildering array of new variants since the emergence of Omicron in late 2021. 1,700 PANGO labels had been assigned to descendant variants and recombinants within “Omicron”.

Based on working definitions updated in March and August 2023, the WHOrecognizes three categories of variants: Variants of Interest (VOIs), Variants of Concern (VOCs), and Variants Under Monitoring (VUMs). The revised (August 2023) criteria on which these are based are summarized below.

Original working definitions: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/historical-working-definitions-and-primary-actions-for-sars-cov-2-variants

Current working definitions (August 17, 2023): https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/updated-working-definitions-and-primary-actions-for–sars-cov-2-variants

III.1.1. WHO Variants Under Monitoring (VUMs)

“A SARS-CoV-2 variant with genetic changes that are suspected to affect virus characteristics and early signals of growth advantage relative to other circulating variants (e.g. growth advantage which can occur globally or in only one WHO region), but for which evidence of phenotypic or epidemiological impact remains unclear, requiring enhanced monitoring and reassessment pending new evidence. If a variant has an unusually large number of antigenic mutations but with very few sequences and/or it is not possible to estimate its relative growth advantage, such a variant can also be designated a VUM.”

III.1.2. WHO Variants of Interest (VOIs)

A SARS-CoV-2 variant:

- With genetic changes that are predicted or known to affect virus characteristics such as transmissibility, disease severity, immune escape, diagnostic or therapeutic escape; AND

- Identified to cause significant community transmission or multiple COVID-19 clusters, in multiple countries with increasing relative prevalence alongside increasing number of cases over time, or other apparent epidemiological impacts to suggest an emerging risk to global public health.

III.1.3. WHO Variants of Concern (VOCs)

A SARS-CoV-2 variant that meets the definition of a VOI and, through a comparative assessment, has been demonstrated to be associated with one or more of the following changes at a degree of global public health significance:

- Increase in transmissibility or detrimental change in COVID-19 epidemiology; OR

- Increase in virulence or change in clinical disease presentation; OR

- Decrease in effectiveness of public health and social measures or available diagnostics, vaccines, therapeutics.

| Figure 3. Legacy nicknames used on social media and based on Greek mythological creature names, alongside ECDC and WHO categorizations. |

More recently, WHO officials have indicated in various communications that a new Greek letter (Pi or Rho) will only be assigned if a variant arises that necessitates a change in public health measures, which was not a requirement under the original criteria. See, for example:

- Why no Pi? Variants are still stuck on Omicron even as coronavirus continues to mutate (CNN)

- The Kraken COVID variant isn’t different enough from other Omicrons to get a Greek letter, WHO official says (Fortune)

III.2. PANGO Lineages

The standard nomenclature for variants in technical contexts is based on the PANGO system that was proposed early in the pandemic (see Rambaut et al. 2020: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41564-020-0770-5; O’Toole et al. 2022: https://bmcgenomics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12864-022-08358-2; https://www.theglobeandmail.com/world/article-how-do-covid-19-variants-get-their-names/). Under this system, lineages are assigned labels according to a suite of detailed evolutionary (genetic novelty, phylogenetic relationships) and epidemiological (transmission, pathogenicity) criteria (https://www.pango.network/the-pango-nomenclature-system/statement-of-nomenclature-rules/):

1. A set of SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences may be considered for the designation of a new lineage name if it exhibits the following essential characteristics:

1a. At the time of designation, the set of sequences is expected to share a single common ancestor and represent a monophyletic or paraphyletic clade in the SARS-CoV-2 phylogeny (see I.1e).

1b. The clade should be distinguished by at least one unambiguous evolutionary event (single nonsynonymous change, insertion/deletion, or recombination event).

1c. The clade should contain a minimum of 5 sequences with high genome coverage. High coverage means that <5% of nucleotides sites in the whole genome (excluding UTRs) are represented by IUPAC ambiguity codes.

1d. The clade must include at least one internal node and therefore cannot be solely composed of a single polytomy. Thus, a lineage is expected to be consistent with a significant amount of onward transmission.

1e. Due to the large size of the SARS-CoV-2 global phylogeny, a quantitative measure of clade support is no longer required (except for that imposed by I.1b)

2. A new non-recombinant lineage designation is expected to also represent one or more events of epidemiological significance.

2a. A non-exhaustive list of possible events are as follows:

(i)The clade may represent inferred movement of the virus into a new country or region (founder event).

(ii) The clade may distinguish successive epidemic waves in the same location.

(iii) The clade may be observed to be growing rapidly and/or strongly increasing in frequency compared to other co-circulating lineages. [This is a departure from Version 1 of the Rules.]

(iv) The clade may be associated with observed or predicted changes in phenotypes including, but not limited to, transmissibility, immunogenicity, or pathogenicity.

(v) The clade may indicate a cross-species transmission event.

(vi) The clade may carry a set of multiple mutations of particular biological interest or concern. Note that, in most cases, the presence of a single specific mutation, by itself, will not be considered sufficient to warrant a new lineage designation.

The stated criteria are considered necessary but not sufficient and non-exhaustive for the designation of a new PANGO lineage, and designations have not been automatic based on meeting specific criteria (though this may change; see https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.02.03.527052v1). Rather, decisions have been made for each proposed new variant by a Lineage Designation Committee. If a PANGO designation is granted, the variant is labeled using an alphabetical prefix (proceeding in sequence A, B,… then AA, AB…; the letters I and O are omitted to avoid confusion with the numbers 1 and 0) and a numerical suffix (e.g., A.1, A.1.1, B.1, B.2). A separate labeling system is used to indicate recombinant (hybrid) variants, in this case beginning with X followed by another letter(s) (proceeding in sequencing XA, XB,… then XAA, XAB…) and containing no numerical suffix except for unambiguous descendants (e.g., XB, XB.1). PANGO lineages may be given new aliases when they would otherwise exceed a maximum length:

In order to avoid excessively long lineage labels, the numerical suffix has a maximum of three hierarchical levels (primary, secondary and tertiary suffixes). Descendants of lineages with tertiary suffixes are assigned to the next available permitted alphabetical prefix, in alphabetical order. This new prefix acts as an alias for the name of the parental lineage. Example: The first named descendant of lineage B.1.1.1 is not named B.1.1.1.1 but is instead named C.1. The prefix C therefore serves as an alias for B.1.1.1.

The use of aliases greatly simplifies PANGO labels for more recently-evolved descendant variants, but also obscures information regarding evolutionary relationships. For example, “DS.1” does not indicate anything about the lineage of variants to which it belongs. For this, it is necessary to drill down through several layers of aliases. For example, DS.1 is an alias for BN.1.3.1.1. BN.1 is an alias for BA.2.75.5.1. BA.2 is an alias for B.1.1.529.2. So, DS.1 = BN.1.3.1.1 = BA.2.75.5.1.3.1.1 = B.1.1.529.2.75.5.1.3.1.1. In order to determine that DS.1 is a member of the BA.2 Omicron lineage and a descendant of BA.2.75, it is necessary to expand the label through two alias layers (which can be done for any variant using Cov-Lineages: https://cov-lineages.org/lineage_list.html). Similarly, the origin of a variant lineage through recombination will be lost once a new alias is assigned (for example, a descendant of XBB.1.9.1 would receive a new letter prefix that does not include X).

III.3. Nextstrain / CoVariants Clades

The criteria used to assign Nextstrain clade labels have been revised over time, and currently include meeting any of the following:

- A VOC or VOI is recognized by the WHO and given a Greek letter label.

- A clade reaches >20% global frequency for 2 or more months.

- A clade reaches >30% regional frequency for 2 or more months.

- A clade shows consistent >0.05 per day growth in frequency where it’s circulating and has reached >5% regional frequency.

Additionally, for points 2, 3, and 4, we require the clade to show multiple mutations in S1 or particular mutations of known biological relevance.

https://nextstrain.org/blog/2022-04-29-SARS-CoV-2-clade-naming-2022

Nextstrain (and CoVariants) clade designations make use of a labelling system consisting of a numerical prefix representing the year in which the clade was designated followed by a letter suffix given in order (e.g., 20A, 20B… 21A, 21B, 21C, 21D). Nextstrain clades represent a small subset of PANGO lineages that meet additional growth or frequency criteria. As it takes time for growth in frequency to be documented, Nextstrain clades are often designated after new variants are first being discussed more broadly (e.g., because they exhibit a potential for high transmission, immune-escape, or virulence but have not yet displayed realized growth).

IV. Variant Names in Biological Context

The net effect of the above naming conventions is that a single variant may have up to four labels: WHO Greek letter (e.g., Omicron), PANGO lineage (e.g., BA.5.2.1.7), PANGO alias (e.g., BF.7), and Nextstrain clade (e.g., 22E). This can be confusing, especially with a rapidly increasing suite of variants being tracked and discussed.

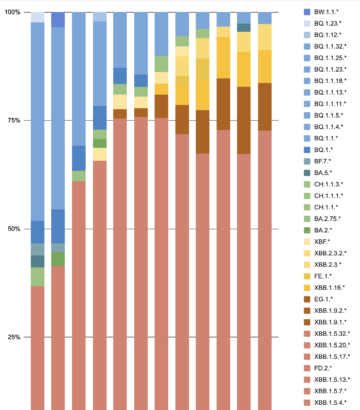

| Figure 4. Multiple names assigned to individual SARS-CoV-2 variants according to WHO, Nextstrain, or PANGO criteria. Source: https://covariants.org/. |

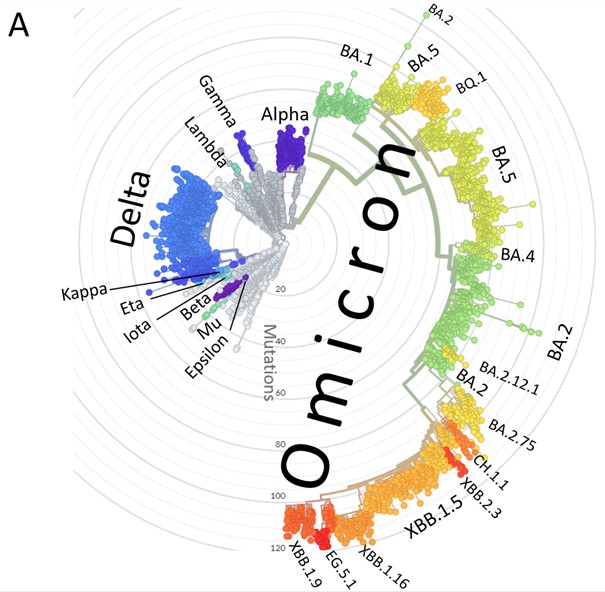

| Figure 5. Phylogeny of SARS-CoV-2 variants showing Nextstrain, WHO, and PANGO labels. Source: https://covariants.org/ based on http://nextstrain.org. |

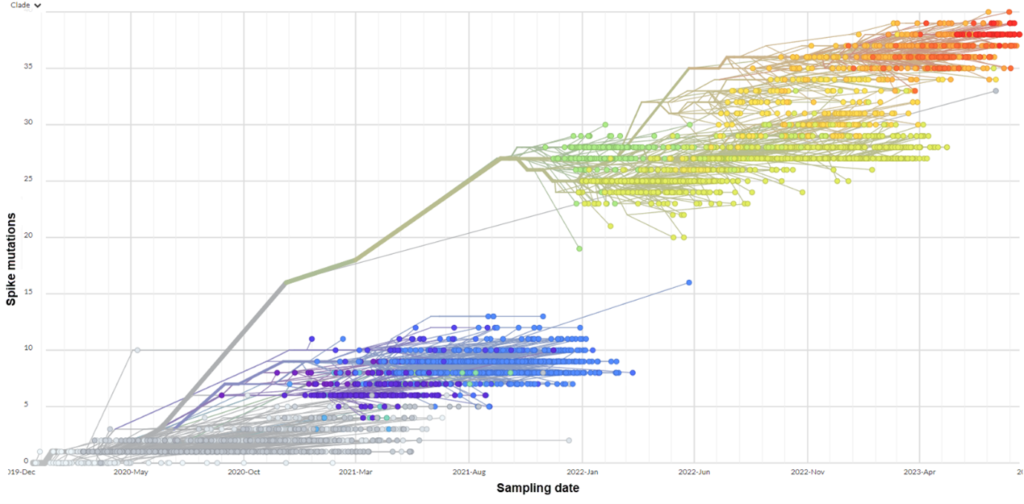

| Figure 5. Diagram depicting mutations and relationships among Omicron variants under discussion in late September 2022. Source: Daniele Focosi (@dfocosi) and Marc Johnson (@SolidEvidence). |

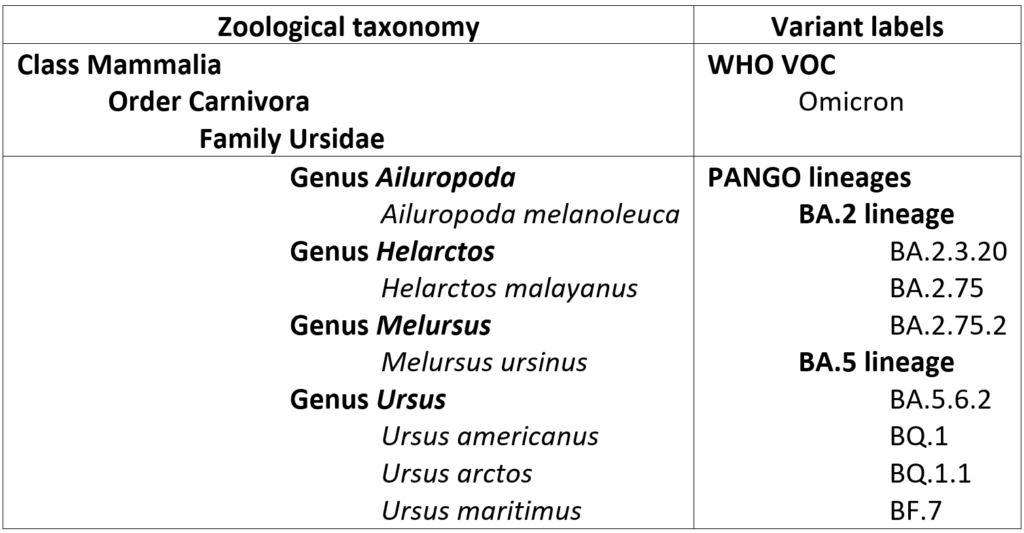

Part of this confusion can be alleviated through clarification of the relevant scale of the various names assigned to a variant. For example, it is apparent that the WHO Greek letter nomenclature is being applied exclusively to high-level evolutionary groupings, somewhat akin to higher level taxonomic groupings in zoological or botanical classification. “Omicron”, then, is roughly equivalent to “Mammalia”, the clade that includes all living placental mammals, marsupials, and monotremes as well as all extinct members of lineages tracing back to their most recent common ancestor. PANGO lineages, by contrast, are akin to formal scientific genus/species designations – that is, each variant has the equivalent of a species name but is also part of a genus along with closely related species.

Of course, species of animals and plants that are commonly encountered or of special interest are often much better known by their common names – informal designations that are used in most non-technical parlance. For example, the species listed above are far better recognized by their common names:

| Scientific name | Common name |

| Ailuropoda melanoleuca | Panda bear |

| Helarctos malayanus | Sun bear |

| Melursus ursinus | Sloth bear |

| Ursus americanus | Black bear |

| Ursus arctos | Brown bear/Grizzly bear |

| Ursus maritimus | Polar bear |

As with animal species, non-technical discussions of variants that are of special interest would benefit from the use of “common names” while discussions among experts will likely continue to use formal names for the sake of precision.

V. A Proposal for Consistent Assignment of “Common Names” (Nicknames) to Variants

V.1. Guiding Principles

The primary objectives of assigning common names to variants are to facilitate broader communication, to reduce confusion, and to accurately reflect the state of ongoing variant evolution of SARS-CoV-2, and identify new variants of potential concern to help communicate about public health guidance and policy (e.g., recommendations for mitigation measures, effectiveness of vaccines and treatments). With this in mind, some core principles can be outlined regarding any system to assign common names and the types of names that may be chosen. Specifically, common names for variants should:

- Be assigned through a transparent, consistent mechanism that can be maintained as new variant lineages continue to evolve.

- Be based on objective evolutionary and epidemiological criteria..

- Reduce confusion in communicating about variant evolution and diversity.

- Be memorable, resonate with the intended audience, be easy to spell and pronounce, be useful in discussions around the globe and in multiple languages, and avoid potentially stigmatizing names.

- Not carry significant cultural or religious associations (e.g., avoid astrological signs).

- Convey the importance of following variant evolution (e.g., no flippant or “cute” names) while also not strongly implying specific public health outcomes (e.g., not suggesting a major wave will occur without additional data).

- Achieve balance between identifying variants that should be given attention while not being used excessively such that they become confusing or lead to disinterest or complacency.

- Be compatible with and complementary to existing nomenclature systems (WHO, PANGO, Nextstrain).

V.2. Criteria for Assigning Common Names to Variants

As with formal names, it is important to define criteria that will form the basis of assigning common names to variants. Some individual criteria may be more compelling on their own, and some may rarely be used if data are not available. Specific thresholds should be narrower than for PANGO lineages but less stringent than for Nextstrain, such that common names are assigned early enough to be useful in emerging discussions.

Examples of probable criteria:

- Prevalence threshold (within countries or globally)

- Growth rate within countries

- Spread among countries

- Divergence (e.g., clearly a new clade)

- Immune evasion and/or ACE binding characteristics based on mutations and/or projected growth rate advantage

Examples of potential additional criteria:

- Severity. It would be best to avoid speculation based only on mutational profile, as many factors influence overall individual and population impacts. However, this may be a useful criterion in cases where a new variant is associated with a rapid early rise in hospitalizations, for example.

- Specific combination of mutations that are of interest due to previously identified variants. This could be useful for highlighting highly divergent or otherwise evolutionarily notable variants, though it is advisable to require some degree of realized importance by measures of this variant before designating a common name.

- Some other defensible reason that a variant is of particular interest (“wildcard”).

V.3. Evaluation Process for the Designation of Common Names

It is proposed that a system similar to that used for evaluating proposed PANGO lineage designations be employed for common names. That is, a proposal would be submitted (e.g., through a web form) that outlines the basis for designating a common name based on the established criteria, which would then be reviewed by a Variant Naming Group.

The process for assigning common names to variants should be straightforward, ideally drawing in order from a pre-determined list of names that meet the stated requirements listed above. It may be desirable to rotate through starting letters (as with names for hurricanes). In special cases, a name other than the next one in sequence could be proposed in order to capture a specific aspect of the variant, though doing this for each variant is overly burdensome.

V.4. Source(s) of Common Names and Embedded Information in Nicknames

There are several possible sources that could be used to create lists of names that will be assigned in sequence. Early informal nicknames have been based on (mostly) Greek mythological creatures, to fit thematically with the formal WHO Greek letter naming system. More recently, names have been drawn from astronomy (constellations, stars, moons, asteroids, exoplanets). Initially, astronomical names were chosen according to a ruleset that indicated “Omicron” lineage (BA.2, BA.5, etc.) and whether a variant was part of a recombinant lineage. However, by August 2023 this was no longer necessary as nearly all variants in circulation were members of the recombinant BA.2 XBB lineage. Common names assigned from “Pirola” (BA.2.86) onward do not follow this prior convention.

A list of common names and corresponding PANGO labels (aliases and full designations) should be kept up to date and made easily accessible.

V.5. Looking Ahead

The current system for designating common names for variants has been developed in response to the challenges of communicating about the evolution of a large number of lineages within the Omicron group. The naming conventions proposed above provide a means of identifying important features within that context, including the Omicron lineage to which a variant belongs and whether it is derived from a recombination event. It is possible that a deeply divergent variant lineage could evolve (e.g., during a long-term infection in an immunocompromised host, through recombination among distant lineages, or by evolving in an animal reservoir and then re-entering the human population). It is expected that such a variant would receive a formal Greek letter label, but additional subvariants that warrant discussion could evolve within that new lineage. In that case, the nicknaming system will require revision, for example by using a different source of nicknames for non-Omicron variants.

VI. Links and Resources

- Nextstrain: https://nextstrain.org/ncov/gisaid/global/all-time

- CoVariants: https://covariants.org/

- CoV-Spectrum: https://cov-spectrum.org/

- Cov-Lineages: https://cov-lineages.org/

- Github PANGO designations: https://github.com/cov-lineages/pango-designation

- Variant visualization tool by Mike Honey: https://bit.ly/40JUzZA

- Variant visualization tools by Raj Rajnarayanan: https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/raj.rajnarayanan

- WHO announcement of Greek letters: https://www.who.int/news/item/31-05-2021-who-announces-simple-easy-to-say-labels-for-sars-cov-2-variants-of-interest-and-concern

- WHO variant categories: https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants

- ECDC variant categories: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/variants-concern

- CDC variant categories: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/index.html

- CDC variant tracker: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions

Last reviewed on March 15, 2023

Share